Saturday, November 29, 2008

Music: The Chinese

But really, besides the fact that Chinese musicians are either fine with being clichéd, or else unaware of it, their concepts of romance are generally sweeter, less sensual, and more pure than their Western counterparts. Whether you hear about love unrequited, or the simple love of a first romance, Chinese music just has that sense of being earnestly, sweetly, sentimental. It's a bit like being eternally youthful, in an emotional sense. Free of worldliness and cynicism.

Monday, November 24, 2008

Philosophies

Your result for The Sublime Philosophical Crap Test...

N-S-R

You scored 100% Non-Reductionism, 33% Epistemological Absolutism, and 44% Moral Objectivism!

Metaphysics: Non-Reductionism (Idealism or Realism)

In metaphysics, my test measures your tendency towards Reductionism or Non-Reductionism. As a Non-Reductionist, you recognize that reality is not necessarily simple or unified, and you thus tend to produce a robust ontology instead of carelessly shaving away hypothetical entities that reflect our philosophical experiences. My test recognizes two types of Non-Reductionists: Idealists and Realists.

1. Idealists believe that reality is fundamentally unknowable. All we can ever know is the world of sense experience, thought, and other phenomena which are only distorted reflections of an ultimate (or noumenal) reality. Kant, one of the most significant philosophers in history, theorized that human beings perceive reality in such a way that they impose their own mental frameworks and categories upon reality, fully distorting it. Reality for Kant is unconceptualized and not subject to any of the categories our minds apply to it. Idealists are non-reductionists because they recognize that the distinction between phenomenal reality and ultimate reality cannot be so easily discarded or unified into a single reality. They are separate and distinct, and there is no reason to suppose the one mirrors the other. Major philosophical idealists include Kant and Fichte.

If your views are different from the above, then you may be a Realist.

2. Realists deny the validity of sloppy metaphysical reductions, because they feel that there is no reason to suspect that reality reflects principles of parsimony or simplicity. Realism is the most common-sensical of the metaphysical views. It doesn't see reality as a unity or as reducible to matter or mind, nor does it see reality as divided into a phenomenal world of experience and an unknowable noumenal world of things-in-themselves. Realist metaphysics emphasizes that reality is for the most part composed of the things we observe and think. On the question of the existence of universals, for instance, a realist will assert that while universals do not physically exist, the relations they describe in particulars are as real as the particular things themselves, giving universals a type of reality. Thus, no reduction is made. On the mind-body problem, realists tend to believe that minds and bodies both exist, and the philosophical problems involved in reducing mind to matter or matter to mind are too great to warrant such a reduction. Finally, realists deny that reality is ultimately a Unity or Absolute, though they recognize that reality can be viewed as a Unity when we consider the real relations between the parts as constituting this unity--but it doesn't mean that the world isn't also made up of particular things. Aristotle and Popper are famous realists.

*****

Epistemology: Skepticism (Idealism or Subjectivism)

In regards to epistemology, my test measures your tendency towards Absolutism or Skepticism. As an epistemological Skeptic, you believe that ultimate reality cannot be known in any objective way. The two categories of Skeptics that my test recognizes are Idealists and Subjectivists.

1. Epistemological Idealists believe that knowledge of ultimate reality is impossible. All we can ever have knowledge about is the world of phenomenal human experience, but there is no reason to suspect that reality mirrors our perceptions and thoughts, according to Idealists. Idealists, then, tend to see truth not as a correspondence between propositions and reality--reality is, after all, fundamentally unknowable--but as a coherence between a whole system of propositions taken to be true. We cannot escape from language or our conceptualized world of phenomena, so we are unable to reference propositions to facts and must instead determine their truth by comparing them to other propositions we hold to be true. As a result of such an idealism, knowledge of any ultimate reality is taken to be impossible, hence the Skeptical tendency of idealism. All our pursuits of knowledge, science included, can only reflect a phenomenal reality that is of our own making. Famous idealists include Kant and Fichte.

If the above did not sound skeptical or idealistic enough to reflect your own views, then you are most likely a Subjectivist.

2. Epistemological Subjectivists, like idealists, believe that all our knowledge is ultimately of our own making because it is filtered through our subjective perceptions. Unlike an idealist, though, a subjectivist doesn't believe in any universal categories of "truth" that apply to the phenomenal world, because each individual can create his own truth. Either that, or he will hold that society or custom creates its own forms of truth. A subjectivist will tend to regard scientific inquiry as a game of sorts--science does not reveal truths about reality, but only gives scientists pseudo-solutions to pseudo-problems of the scientific community's own devising. It is a type of puzzle-solving, but the puzzle isn't of reality. The definition of truth to a subjectivist may be one that recognizes a proposition's usefulness to an individual. William James is one such subjectivist, who believes that we can "will to believe" certain propositions so long as we would find them useful. The example he gives is being found in a situation where you must leap over a chasm in order to survive. The true belief, in such a situation, is that the leap will be successful--this truth is certainly more useful to us, and in believing the truth we become more willing to commit to the jump and make it successful. So, in essence, knowledge of reality is possible for a subjectivist because they never make reference to any objective reality existing outside of our own perceptions and beliefs--we can have knowledge of reality through having knowledge of ourselves, and that is all that we should ask for. Famous subjectivists include Kuhn, Feyarabend, and James. Another famed critic of Absolutism is Hume.

*****

Ethics: Relativism (Subjectivism or Emotivism)

My test measures one's tendency towards moral Objectivism or moral Relativism in regards to ethics. As a moral Relativist, you tend to see moral choices as describing a subject's reaction to a moral object or situation, and not as a property of the moral object itself. You may also feel that moral words are meaningless because they do not address any empirical fact about the world. My test recognizes two types of moral relativists--Subjectivists and Emotivists.

1. Subjectivists see individual or collective desires as defining a situation's or object's moral worth. Thus, the subject, not the object itself, determines the value. Subjectivists recognize that social rules, customs, and morality have been wide-ranging and quite varied throughout history among various cultures. As a result, Subjectivism doesn't attempt to issue hard and fast rules for judging the moral worth of things. Instead, it recognizes that what we consider "good" and "right" is not bound by any discernable rule. There is no one trait that makes an act good or right, because so many different kinds of things have been called good and right. In regards to the definition of "good" or "right", a Subjectivist will tend to define it as whatever a particular person or group of people desire. They do not define it merely as "happiness" or "pleasure", for instance, because sometimes we desire to do things that do not produce pleasure, and because we don't consider all pleasurable things good. Furthermore, Subjectivists recognize the validity of consequentialism in that sometimes we refer to consequences as good and bad--but they also recognize that our intentions behind an action, or the means to the end, can also determine an act's moral worth. Again, there is no one rule to determine these things. Hence the relativism of moral Subjectivism. The most well-known of the subjectivists is Nietzsche.

If that didn't sound like your position, then you are probably the other variety of moral Relativist--the Emotivist.

Emotivists are moral Relativists only in a very slanted sense, because they actually deny that words about morality have any meaning at all. An Emotivist would probably accept Hume's argument that it is impossible to derive an "ought" from an "is"--no factual state of affairs can logically entail any sort of moral action. Furthermore, a emotivist's emphasis on scientific (and hence empirical) verification and testing quickly leads to the conclusion that concepts such as "good" and "right" don't really describe any real qualities or relations. Science is never concerned with whether a particular state of affairs is moral or right or good--and an emotivist feels much the same way. Morality is thus neither objective or subjective for the emotivist--it is without any meaning at all, a sort of vague ontological fiction that is merely a symbol for our emotional responses to certain events. Famous emotivists include Ayer and other positivists associated with the Vienna Circle.

*****

As you can see, when your philosophical position is narrowed down there are so many potential categories that an OKCupid test cannot account for them all. But, taken as very broad categories or philosophical styles, you are best characterized as an N-S-R. Your exact philosophical opposite would be an R-A-O.

Wednesday, November 19, 2008

Why doesn't time listen when I say stop?

It's naive and cliched perhaps, especially when all nice, clean new things eventually get stained and dirty with use. Mistakes are made, and cannot be erased.

Perhaps it's tempting fate to say this, but I don't think I made too many mistakes (edit: I mean major mistakes, the kind that make you go 'What was I thinking?' when you think back on them. Not the making-funny-faces-in-lift-mirrors-when-the-door-opens sort) this year. I think I was spending to much time dwelling on the mistakes of the past, trying to recoup my losses, I suppose.

In the last leg of this transitory phase, before I leave on my jet plane, I want to experience something I've never experienced before. Too bad it's too late to plan something like climbing a mountain or something.

Maybe next year.

Monday, November 17, 2008

Thursday, November 13, 2008

Murakami on the bus

Wednesday, November 12, 2008

True Lie

Did you notice that two theories of truth were employed to build the lie? In establishing how to lie, I made two statements:

- You need to create a system in which everything coheres.

- Your lies need to be consistent with what apparent reality.

The second is the correspondence theory of truth. This means that the proposition you make has to correspond to a factual reality. Like what I said before, in order to lie successfully, your story has to agree with certain witnessed facts. This will make it much more believable, because once someone knows that some things you say are true, and if your story tends to make logical sense, people will tend to believe you.

The third thing that I mentioned was Ockham's razor. In other words, keep your attempts at explanations as simple as possible, given all the accepted facts. In the case of a lie it's more believable. In the case of truth, it's more likely to be true. We only need to look at the elegance of physics formulae to see this case in point.

It would seem as if truth were intrinsically linked in falsehood. But wait, you say. You disagree, similarities extend only up to the fact that you want to make the lie as truthful as possible in order to be believable. Yet when we look at the way knowledge is discovered, we can only admit that we are as good as our best guess. The only difference between truth and prevarication, as we know it, is that in a lie, we know something that the other person does not, and attempt not to include that fact in our explanation.

When we attempt to discover the truth, we first take into consideration the preexisting conditions. We imagine the situation from various angles and make guesses as to the most likely explanation. Indeed, until we have rigorously tested our theories, we can hardly claim them to be more than conjectures, or propositions that we would like you to believe. We might even go as far as to say that until they are proven true, they might be considered to be lies. The ability to lie comes from these same skills.

Not to mention, so-called accepted "truths" have often proved false. There is the infamous, and over-used example of the ancient belief that the earth was the center of the universe, or that the earth was flat. We now know that this is not so. However, they made claims that best fit the situational evidence. Although some data was not perfectly in agreement with the claims, one can hardly say that in the past, the great thinkers of the era were lying to us, or falsifying fact.

I'm not saying that deliberate lying is morally acceptable. Rather, I put it to you that the line between truth and lie comes not so much a clear-cut distinction, but as the fuzzy intersection between two polarly opposite, yet infinitesimally different sets. It is this dichotomisation which knowledge depends on, like cells, to go forth, be fruitful, and multiply.

Which makes me wonder whether Adam and Eve's biggest sin was to taste of the forbidden fruit, or deny it (as you might have guessed, my next post in the theme will be on denial).

Tuesday, November 11, 2008

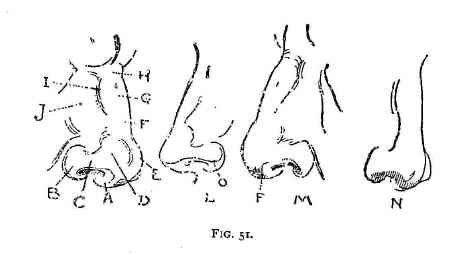

How did the Jamaican grow a Jewish nose?

There are a number of reasons for nose growth. As you have probably already read in Pinocchio, it can grow from lying:

At this third lie, his nose became longer than ever, so long that he could not even turn around. If he turned to the right, he knocked it against the bed or into the windowpanes; if he turned to the left, he struck the walls or the door; if he raised it a bit, he almost put the Fairy's eyes out.

Whether this is true for people or not, I leave for you to decide. I can only tell you that this blog is named after the famous wooden puppet for a reason. I can also say that my nose is a rather prominent feature on my face. From the side, due to a lack of endowment in the vitally important region below my face, one might even say I looked like a nose on a stick. Again, I won't state explicitly whether I'm the lying sort, but there certainly do seem to be a lot of posts on the subject. Anyway, my nose has certainly grown bigger over time.

Since I will not disclose further details on my habits in deception, I shall suggest a number of other reasons, which I shall claim to be closer to the truth.

The first reason is genetics. Obviously, your parents' appearances and the genes which code for them will play a part in determining what you will look like. Genes also play a part in determining how you will grow. As a friend of mine who's studying optometry claims, you can't really help how you grow. Whether you become short-sighted or long-sighted depends on the depth of your eyeball, and that depends to a large extent on your genes. Similarly, whether your nose grows disproportionately larger as you grow older and bigger, as mine has, also depends on whether your parents have been kind enough to endow you with the best of both genes (in my case it was the worst).

The second reason is muscle activation. There are two kinds. One is active, or unassisted, where you use your nose muscles alone to move your nose. You can move your nose up and down, bunny-style, wrinkle your nose, or isolate movement of your left and right nostrils. You may also flare your nostrils. I have yet to discover and master more nose movement, although there have been reports of people who can perform feats such as nose-wriggling. Such movements will result in the building of the muscles of the nose and a resulting increase in size.

The other is passive, or assisted, where you use other parts of your body, such as your hands, to pull at or move your nose. The act of pulling one's nose also stimulates circulation to the area. Supplied with more blood, it is likely to promote healthy, and sometimes vigorous, tissue growth. Repeated contact with your nose if you wash your face too frequently may also result in over-stimulation and growth.

The third reason is injury or illness. If you are injured, or if you have sinuses or a blocked nose, inflammation is a likely result that will temporarily increase the size of your nose. Alternatively, a broken nose that is poorly healed may result in a misshapen and enlarged nose.

In short, who nose how your nose will grow? I might be pulling your leg, or lengthening my nose, but as I have mentioned before, a good lie is always based on observed fact.

Friday, November 7, 2008

Lying on a bed of nails

People always say that you should tell the truth. It's not exactly in the ten commandments, although there is something about not giving false testimony about your neighbour. But what happens when not lying is bad? What happens when to tell the truth is to contradict other moral values?

It's so easy to say that we should tell the truth, and admire those who are courageous enough to tell the truth and face the consequences. But it's not always that simple. I wish I had the strength of conviction to stand up for myself and my causes and beliefs and tell the truth. But when you threaten me with causing others unnecessary worry or (as cliche and unfashionable as this sounds) disobeying the people you love, and who are supposed to know what's best, I feel like to tell the truth is a bigger sin than to lie (I know it seems insinuating that I'd lie to shield others, but really, I'm not trying to say that. I freely admit I lie for my own gain more than anything else. It's the moral sense of being caught between Scylla and Charybdis I'm trying to emphasize).

But then again, you can't just tell one lie and have done with it. You need to lie again to be self-consistent. And again, and again, and again. You need to create a system in which everything coheres. Your lies need to be consistent with what apparent reality. It's like Ockham's razor, except that instead of the simplest explanation being the truth, the simplest explanation that can best fit certain witnessed points in history.

The easiest on your conscience is to avoid having to tell the truth and let the other person assume an explanation on his own. Usually all you have to do is present the situation in a certain light, such that the points witnessed would tend to fit a certain explanation.

However, it often isn't so simple. In order to present your case in this way, you need to tweak reality a little. Take the case where you've sneaked off to eat ice-cream when you were not supposed to. You might get away with saying that you are going around the vicinity of the ice-cream parlour without actually mentioning you are going for ice-cream. If, for instance, it happens to be near a bookshop, the person you have lied to might assume you've gone to browse books. Once he attempts to confirm it with you, you need to act like you haven't heard him and make your escape ASAP, or you could change the subject. Either way, you need to tweak the reality that you've heard what he said, and be evasive.

It gets worse. You might think that after the one lie, you are home free. As I mentioned, this most certainly isn't the case. The amount you have to lie in order to cover up increases exponentially with the seriousness of the lie. Going back to the ice-cream incident, you might find that the person you lied to (A) might have gone and chatted with B, who was at the bookshop. You would then have to find an explanation for the fact that B didn't see you there. In other words, instead of directing dear old Ockham's razor to cut it's way to the truth, you will have to redirect it to bypass the truth, in favour of a more palatable lie.

Most of the time, you can get away with lies that just graze past the truth, like saying 'we must have missed each other' and being non-specific. Often we have mental caveats that we use to defend the lie as being at least partially true (for instance, you would definitely have missed B if you were never at the bookshop). But there are really only so many silent caveats that we can add to our lies, particularly when people ask questions that are all to close to the mark. In order to keep your lying consistent there will be times when you have to say something that directly contradicts historical events, and those are the worst kind. For instance, suppose C, someone working at the ice-cream parlour, ran into A, and told A about seeing you there. You would have to tell A that C saw the wrong person, or that you were walking across the ice-cream parlour to the toilet.

I confess, I eat too much forbidden fruit. Wait, I mean ice-cream.

Sunday, November 2, 2008

You need fillings if you have tooth decay.

Sometimes it seems like experiences, rather than filling a void, only expose a cavity that was hiding in the dark. A longing you never knew you had (or perhaps you know you never should have). A dream you know will never come to pass. A moment of ephemeral bliss that was never meant to last.

The other day Cherie said something interesting that resonates along this thread. Apparently,

"...some scientists claim there is no such thing as tears of happiness. ... They explain that it takes enormous energy to repress our tears. Then seeing the happiness of others, pent-up sadness and anxiety are discharged. In life, happy endings are the exception, and when one occurs, it stirs up anxieties about the past...the real world isn't as happy as the one we want to see."So when we cry because of something beautiful, or wonderful, it's because of some deep-seated longing that can never be fulfilled. Somewhere during the process of maturation, cavities for Prince Charmings and Happily Ever Afters (or in my case, perfect prima ballerina assolutas) are created but will not likely be filled. We don't cry because we're happy. We cry because there's a cavity that never got filled.

And if there's an emotion that alerts us to our cavities, it's loneliness.

Saturday, November 1, 2008

We're all in this together (=

I loitered until I was amongst the last left, and somehow I just couldn't bring myself to leave Dover. It's funny; I didn't really expect myself to be this nostalgic, especially since quite a few of the people who were significant to me weren't there. Cheryl in Cornell, Ally in Shanghai... The sense of diaspora was just tangible over the chatter and nostalgia.

I only wished I could have gotten the chance to talk to everyone I wanted to.